Trigger warning: this article discusses suicidality and abuse.

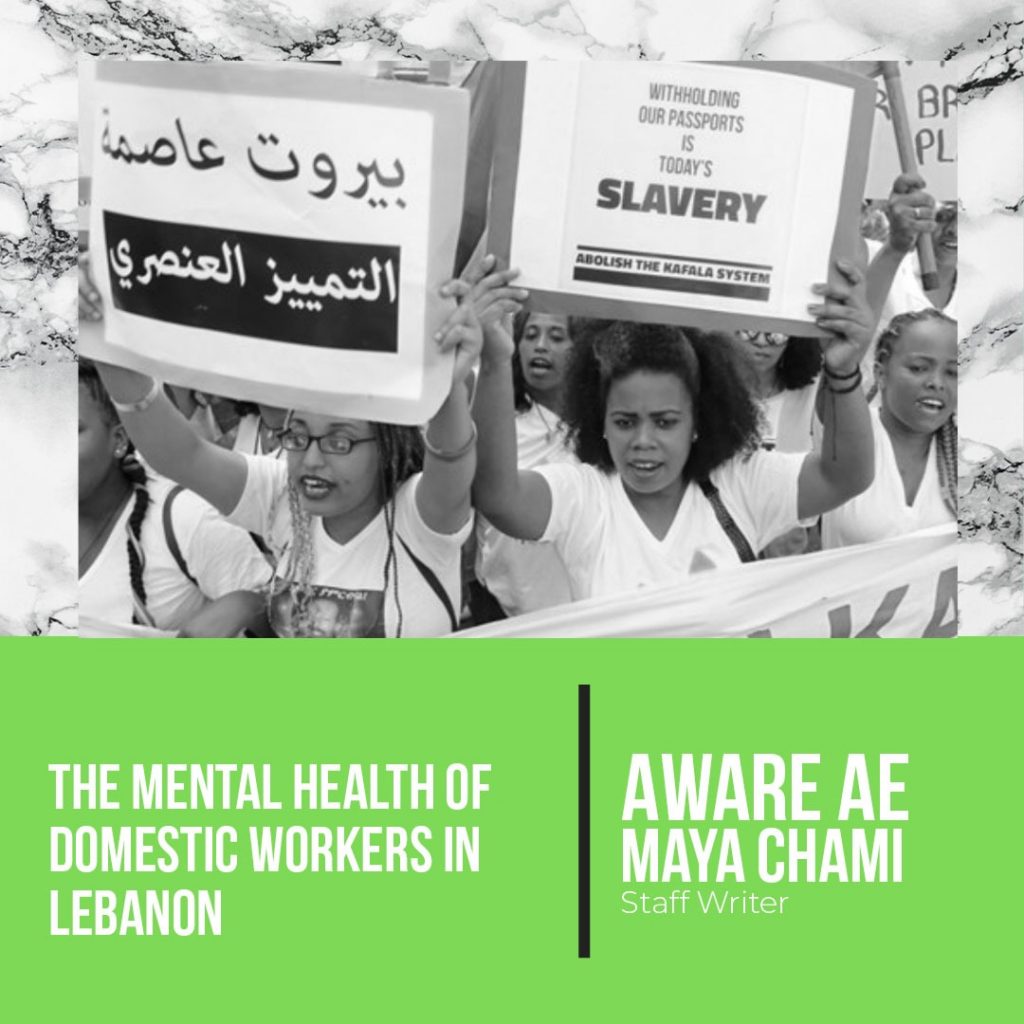

The mental health of migrant domestic workers is at an all-time low in the face of the coronavirus outbreak due to the ongoing systemic oppression, racism, and abuse they constantly face at the hands of the Sponsorship (Kafala) system in Lebanon. Unfortunately, this is not a new phenomenon that is just being revealed. The sponsorship system is a modern slavery system that has been around for a long time, oppressing helpless migrant workers, deteriorating their mental health, and leading them to suicide. The coronavirus outbreak simply prompted the immense increase in attempted suicides and a further deterioration of mental health, due to increased oppression and abuse.

The Sponsorship (Kafala) System

The Kafala system was introduced in the 1950s in the Gulf Cooperation Council, in addition to Lebanon and Jordan. Ironically, this was around the time that slavery was abolished in many GCC countries. There was a need for an alternative system to secure labor from foreign countries; hence, the sponsorship system was introduced. The sponsorship system works in this way: a migrant worker needs to be sponsored by an individual residing in the country or a governmental agency to be able to enter the country and work there. The sponsor takes full responsibility for the migrant worker – both legally and financially – during a period that could take approximately two years. In addition, the sponsor signs a contractprovided by the Ministry of Labor detailing all this.

One can clearly see the issue at hand just by what the sponsorship system constitutes. A migrant worker must be sponsored to be able to enter and work in a country. All rights become property of the sponsor without taking the workers’ personal preferences into account. Even the contract period is not to the benefit of the worker. If a migrant domestic worker decides that they no longer want to work for the house that they were sent to, they are either forced to stay working until the contract ends or allowed to leave at the expense of using their own profit to buy a plane ticket back to their country. This is only a portion of the abuse that await migrant domestic workers.

Migrant Domestic Workers and the Kafala System in Lebanon

Migrant workers come to Lebanon with the impression of working with dignity, only to discover that their rights are confiscated and abused. Their passports are taken away; they often work overtime and are not allowed to sleep before they finish their tasks; the constant racism they face is undeniable and revolting; and, of course, sometimes, they even endure physical, sexual, or emotional abuse.

Their basic right of walking around freely becomes dependent on their ‘Madame’ – whether they are allowed to leave the house (to which the answer is almost always no) or not. The food they eat is, oftentimes, leftovers. With no ID or passport, even when they try to run away from their abusive employers, they would face legal repercussions when the real problem is clearly overlooked.

A film, Mtallat Baladi Assil, introduced by ALEF – an NGO that works towards the rights of people – details the morbid reality that domestic workers go through in Lebanon. The film displays a number of instances through which migrant domestic workers are abused. It shows the severe paranoia and racism inherent in many individuals that automatically associate a foreign domestic worker with a robber, or that dehumanize the foreign domestic worker by referring to him/her as a commodity that can be bought or sold. Another essential component of the film is that it shows that there are now certain NGO helplines for when domestic workers are in need to call them in emergency cases, like suffering abuse or needing other forms of assistance. However, it outlines what these helplines lack: proper language that the domestic workers can understand and a clear definition to what these helplines are used for.

The current economic problems in Lebanon have also prompted financial abuses, with employers not willing or able to pay domestic workers in dollars. These abuses are yet another addition to the list of never-ending oppressive measures being used.

The Sponsorship system works to reinforce all these abuses that infiltrate the daily lives of domestic workers. What we see taking place is an intersectional oppression: oppression on the basis of sex, class, and race. The migrant domestic workers are colored women coming from a disadvantaged background, and this gives them the first-class seat to systemic oppression.

The Mental Health of Migrant Domestic Workers in Lebanon

The incessant abuse that migrant domestic workers in Lebanon face takes a toll on their mental health so much that they end up trying and, in some cases, succeeding to commit suicide. Since the March coronavirus lockdown alone, Lebanon has witnessed 1 death of a domestic worker, another attempted suicide, and a third undergoing psychological problems.

The heartbreaking story of Faustina Tay’s suicide touched many hearts and enraged advocators for domestic worker rights. Tay had come to Lebanon with high hopes of making money and helping her family back home. However, life had other plans. Upon reaching Lebanon, she had her passport confiscated and was subjected to many forms of abuse by her sponsor. A few months later, in March 2020, she was found dead. The police ruled it as a suicide, although there are certain unanswered questions about her death.

One month later, another domestic worker tried to attempt suicide by throwing herself from a window. According to the Enough Violence and Exploitation (KAFA) organization’s investigation, the domestic worker was suffering from mental health problems, and this prompted her attempt at suicide. Around the same time, KAFA was phoned and informed of a domestic worker sitting naked on a sidewalk in Beirut. She was found to be in psychological distress.

The sponsorship system in Lebanon is an ongoing deadly cycle. It takes in helpless, desperate domestic workers and traps them. Domestic workers, upon entering Lebanon, lose their sense of identity, and the conditions they are forced to work in do not help one bit. They find their rights being stripped, along with their dignity, and become forced to work in horrible conditions. The relentless discrimination and oppression intensify their hardships, dwindling their mental health in the process, and leading them to make life-threatening decisions. It is difficult to learn of ordinary people being humiliated and deprecated, being driven to want to end their lives. It is hurtful to know that all this is often for certain economic gains and power – nothing else.